Financial Times Supplement Watches & Jewellery

November 10, 2013

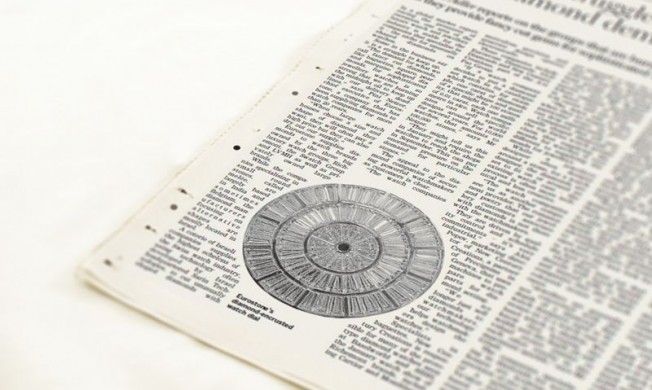

Claire Adler reports on the groups that are burning the midnight oil as they provide fancy cut gems for sophisticated Swiss watches

In a global market experiencing the pressures of recession, one area of the luxury watch and jewellery industry is stable for the companies that specialize in it – the niche for unusually shaped diamonds on watches.

Some in the business say it is a struggle to keep up. “The demand for what we call fancy cut diamonds, like baguettes, square, pear and marquise shaped diamonds, for sophisticated jewellery watches is so strong that we are burning the midnight oil to keep up with our delivery deadlines,” says Pini Netzer, chief executive of Eurostone, a company that has been supplying diamonds to watch companies for more than 20 years.

“When large watch houses choose a size and shape of diamond they want, they will often pay a high price but they can also dry out our supply.”

Eurostone supplies diamonds to watch brands owned by the three big luxury watch groups, Richemont, the Swatch Group and LVMH as well as privately owned large brands. While the companies specialising in small round stones, called melée, are largely based in India and sometimes Belgium, the diamond manufacturers focusing on alternative shapes are mostly located in Israel.

A coterie of Israeli companies supplies the highest echelons of the Swiss watch industry, using technology often developed by Israel headquartered Sarin Technologies, to cut unusually shaped diamonds with meticulous precision and generate design options electronically.

“If a watch company decides to put a diamond-set watch in its catalogue which contains, for example, one carat of diamonds of a specific shape and quality, that might be 100 stones of 0.01 carat, each one millimeter in size. Watch companies can sell specific designs around the world for several years. For 10,000 watches, that amounts to a 100,000 stones,” says Mr. Netzer.

“They might tell us this in January and require the watches to reach the shops in September. This can put enormous pressure on the demand for particular stones.”

The appeal to the diamond companies of securing powerful watchmakers as customers is clear. “The watch companies are prepared to pay for the best, they are extremely selective and they belong to large groups, which means we can trust them as good payers,” says Mr Netzer, whose company specializes in fancy cuts of between 0.02 carats and one carat. “The down side is that, when they no longer want a particular stone, its price can drop significantly.”

Companies that sell unusually shaped diamonds to the top Swiss watch groups claim that supplying diamonds for watches is very different to supplying diamonds for jewellery.